In this modern age, a great deal of hooplah is made over the idea of ‘gamifying’ work, exercise, or tasks we need to do. Yet it rarely works as well as the experts would argue, and only certain people seem to be able to make it work at all, let alone long term. I don’t think it’s because we are failing or bad at it. No, instead, I have a theory that strikes at the heart of the concept, and yet may suggest a solution.

(Neat way to keep you reading, eh?)

The secret to gamifying – and games in general – is the reward for completing the game or task, or even ‘winning’. In many games, ‘winning’ itself is defined by the reward we receive – money, a medal, a trophy, bragging rights, etc.. Without the reward, finishing soon begins to seem rather hollow. So we’re taught that, in order to ‘gamify’ something in our life, we need to come up with some sort of ‘action-reward’ system. If we exercise today, we get to have that tasty energy drink. If we finish the contract before it’s due, we get to go out for drinks with our bestie, or whatever. We have to reward ourselves.

Unfortunately, it’s right there that I think the system breaks down for most people. Rewarding ourselves rapidly seems to lose its appeal and ceases to be fun for most people. And I think I know why.

Anticipation and surprise.

You see, whenever we play a game – any game – we anticipate the prospect of winning. Winning brings rewards, so the anticipation gives us that little dopamine hit, and winning then feels even better. So anticipation is key. But there’s another element, and I think it’s even more vital. Surprise.

If we know the outcome of the game is assured, it’s not as much fun. But if we also know the prize for winning is guaranteed, it’s also not quite as much fun – often even less so. There’s no surprise. So when we gamify something, we go into it knowing that the outcome – the winning – is reasonably assured, and the outcome for winning is absolutely guaranteed

So why are other games so much more fun?

.Because, there’s the element of surprise.

No matter how formal the game, first of all there’s the chance we may lose altogether. Winning doesn’t just rely on how well WE play, it also depends on how well THE OTHER SIDE plays. Winning isn’t assured. On top of that, no matter how much we trust the game, in the back of our minds is always that question – however tiny – of ‘will I actually get the promised reward?’ Maybe the other side will renege and not offer the promised winnings. Maybe the organizers will fail to follow through. Maybe any number of a million things might happen that will make the victory pointless. And when none of that happens, we’re delighted, and the win seems sweet, because we weren’t absolutely assured of getting it.

This is why ‘gamifying’ doesn’t – usually – work as well as it should.

Though, this also suggests a possible solution. A way of ‘upping your game’, if you don’t mind the unintentional pun.

Follow the guidelines for gamifying, yes – but get someone else involved. Either find someone doing the same or similar things and test yourselves against each other (‘I wrote ten thousand words this week, how about you? Oh, you wrote eleven thousand? Okay, then I’m buying the beers at the pub this week.’). Or let your partner measure your progress and think up the rewards (Okay, honey, since you did all your exercises and did ten more pushups this week than last, I’m taking you to your favorite store on Saturday for a little shopping).

In other words, insert a little surprise in your gamifying to go along with the anticipation.

Comment if you like and let me know if this rings true and if my solution works for you.

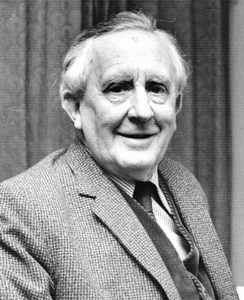

“I have claimed that Escape is one of the main functions of fairy-stories, and since I do not disapprove of them, it is plain that I do not accept the tone of scorn or pity with which ‘Escape’ is now so often used. Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls?” – J.R.R. Tolkien

“I have claimed that Escape is one of the main functions of fairy-stories, and since I do not disapprove of them, it is plain that I do not accept the tone of scorn or pity with which ‘Escape’ is now so often used. Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls?” – J.R.R. Tolkien